Radiopharmaceuticals are an expanding trend, with market size predictions doubling within the next 10 years to $13.67B in 2033. In this blog, we will go over the basics of nuclear medicine and answer the questions: what are radiopharmaceuticals? And how does nuclear medicine work? Radiopharmaceuticals play an important role in precision and personalized medicine. The last few years have been marked by large acquisitions in radiopharma, fueling the development of these diagnostic and therapeutic drugs. At TRACER, an imaging CRO, we use nuclear imaging in clinical trials and conduct dosimetry studies, Phase 0, 1, and 2 for radiopharmaceuticals. Contact us to learn more about our services.

Contact TRACER

What are radiopharmaceuticals?

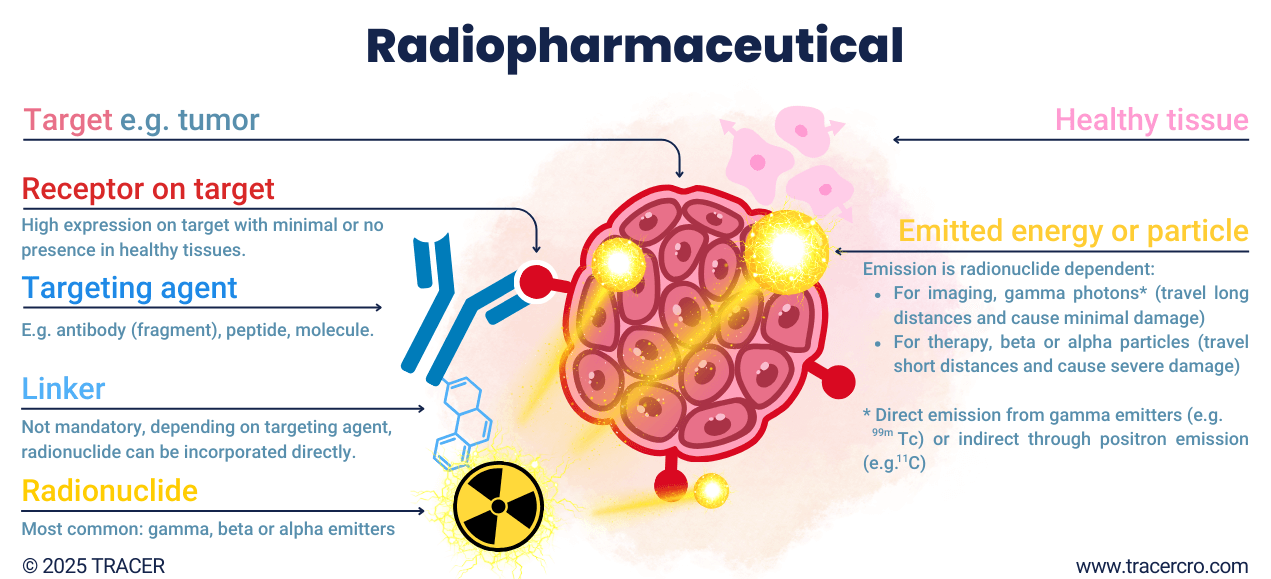

What are radiopharmaceuticals? Radiopharmaceuticals consist of a radionuclide connected to a targeting agent with an affinity to the target. For example, a tumor. Depending on the coupled radionuclide, the type of radiation allows for imaging and/or treatment. The targeting agent is used for its carrier and binding properties. Biodistribution and binding-specificity are based on the targeting agent. Many types of substances can be used as a targeting agent. Think of glucose which can be radiolabeled with fluor-18 to track glucose metabolism. There are some exceptions where the radionuclide itself binds to the targets, without the use of a targeting agent. These radionuclides are indicated as organ seekers. For example, iodine is naturally taken up by the thyroid gland, or radium and fluorine accumulate in bone.

Radiodiagnostics and -therapeutics

Radiopharmaceuticals can be injected, infused, inhaled, ingested, or delivered topically. Once in the body, gamma radiation can be picked up by cameras for imaging. When used as therapeutics, the damaging effect of beta or alpha radiation can be used to destroy the targeted cells. You now know the basics of nuclear medicine, let’s take a closer look at the various radionuclides used and how they differ.

Not all radionuclides are equal

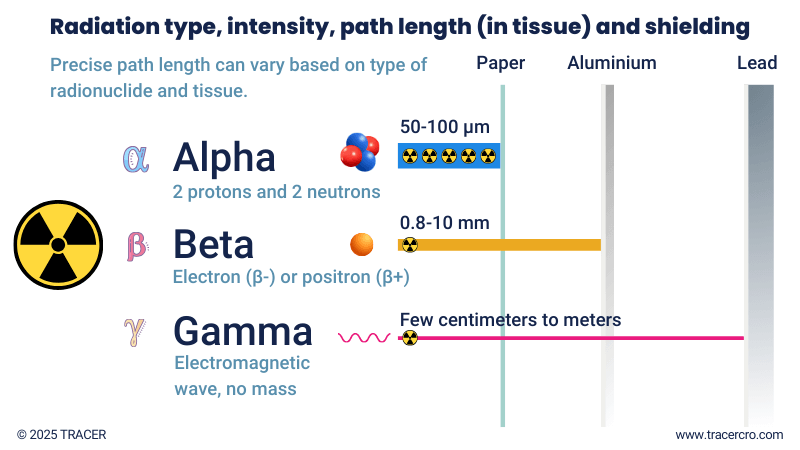

Not all radionuclides are equal. Radionuclides differ by type of decay and emissions they produce. Common categorizations for types of decay are alpha, beta, and gamma. Good to know: a single radionuclide can decay via alpha or beta decay but can also release a gamma photon. For example, iodine-131 is both a beta and gamma emitter.

Emission can be energy in the form of electromagnetic waves, as in gamma and X-ray, or particles as in neutrons, protons, positrons, and electrons. The energy transferred to the traversed medium (e.g. tissue) by these emissions differs. This is expressed in Linear Energy Transfer (LET). LET is measured in units of energy per unit distance, typically in kilo electron volts per micrometer (keV/μm). It represents the amount of energy transferred per unit length of the path of the radiation.

Table: Alpha vs beta vs gamma

(scroll right →)

|

|

Alpha particles |

Beta particles |

Gamma |

|

Ionizing density |

Densely |

Sparsely |

Sparsely |

|

Path length in tissue (approx.)* |

50–100 µm |

0.8–10 mm |

N.A. |

|

LET low/high |

High |

Low |

Low |

|

Example radionuclides** |

Radium-223 (223Ra), Actinium-225 (225Ac), Thorium-227 (227Th), Lead-212 (212Pb) |

Iodine-131 (131I), Yttrium-90 (90Y), Samarium-153 (153Sm), Strontium-89 (89Sr), Lutetium-177 (177Lu) |

Iodine-123 (123I), Iodine-131 (131I) Technetium-99m (99m Tc), Thallium-201 (201Tl), Gallium-67 (67Ga), Indium-111 (111In), |

|

Genotoxic and carcinogenic |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Probability of cell kill |

Higher |

Moderate |

Lower |

|

Size |

Large |

Small |

No mass |

* Exact values depend on individual radionuclides and type of tissue. You may find different values in literature.

** Most radionuclides emit multiple types of radiation. They are classified here based on their main type. E.g. many radionuclides that emit beta or alpha particles also emit gamma rays after the main type of decay.

Gamma rays

Beta and alpha emitters are used for therapeutic purposes. The emitted particles contain both energy and mass. Contrary to gamma photons, which only exist as energy and have no mass. Gamma rays can be transmitted directly as a form of decay or as a result of the decay of alpha and beta-emitting radioisotopes. Positron decay indirectly produces two gamma photons when the emitted positron collides with an electron in the body. The suitability of a radionuclide for (quantitative) imaging depends on its gamma rays and their energy.

How does nuclear medicine work

Nuclear medicine uses radionuclides for diagnosis and treatment. For imaging, different gamma-emitting radionuclides can be used. For treatment, the damage caused by beta and alpha emitters is intentionally used. Alpha particles are the heaviest and travel a short distance before losing too much energy. All of their energy can be released in the proximity of a few cells, causing greater cell damage in a targeted region compared to other radiation. Since gamma electromagnetic waves don’t have mass, they travel more easily through matter and can be picked up by gamma cameras outside the body.

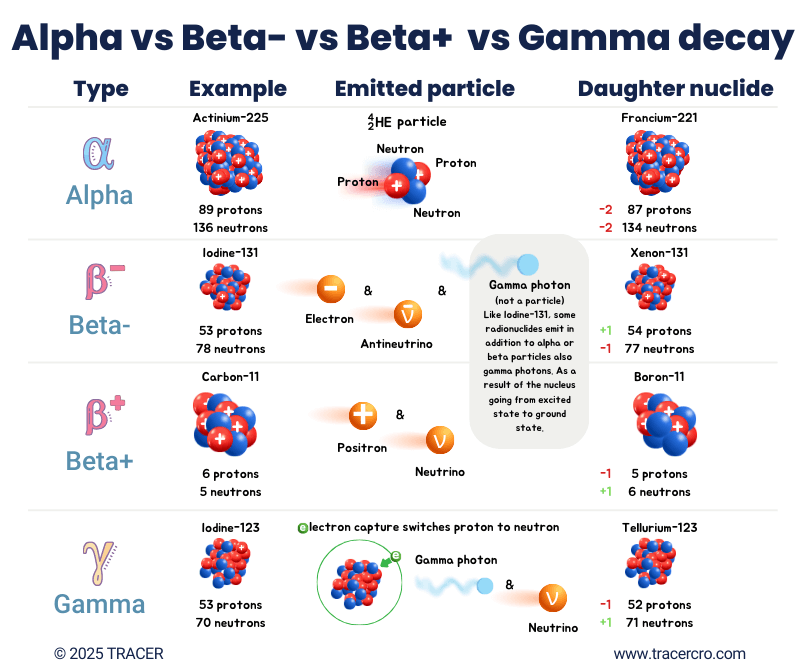

Types of decay: comparison of alpha, beta-minus, beta-plus, and gamma decay

In the figure below are the different types of decay visually explained.

(scroll right →)

|

Decay Type |

Change in Protons |

Change in Neutrons |

Change in Mass Number |

Change in Atomic Number |

Emitted Particles |

Usage |

|

Alpha |

-2 |

-2 |

-4 |

-2 |

Alpha particle (⁴₂He) |

Used for therapy |

|

Beta-Minus (β⁻) |

+1 |

-1 |

0 |

+1 |

Beta particle (electron + antineutrino) |

Used for therapy |

|

Beta-Plus (β⁺) |

-1 |

+1 |

0 |

-1 |

Beta particle (positron + neutrino) |

Used for PET imaging |

|

Electron capture |

-1 |

+1 |

0 |

-1 |

Gamma photon + neutrino |

Used for SPECT imaging |

Gamma radiation is not fully included in this table. The energy state of an element stabilizes by emitting gamma photons, this may happen after a process called electron capture or after other types of decay. A gamma photon can be released to get rid of excess energy, moving the nucleus from an excited energy state to a ground state. The auger effect, a possible result of decay, is excluded from this table but is hereby mentioned for completeness.

Radionuclide vs radioisotope vs radiopharmaceutical

The terms radionuclide and radioisotope are used interchangeably for radioactive substances. They indicate exactly the same but differ in the context in which they are used.

- The term “radionuclide” can be used for all atoms that emit nuclear radiation.

- The term “isotope” is used to indicate different versions of a specific element, all having the same number of protons but a different number of neutrons.

- The term “radioisotope” is used when such an isotope emits nuclear radiation — because of this, the term radionuclide may also be used.

- The term radiopharmaceutical is used when a radionuclide is used as (part of) a drug.

Element vs isotope vs radioisotope

For a better understanding, let’s look at the difference between elements, isotopes, and radioisotopes. The name of an element and its atomic number — as known from the periodic table — are defined by the number of protons in its nucleus. Alpha, beta, and in some cases, gamma decay will change the number of protons and/or neutrons.

- When the number of protons changes, it becomes a different element.

- When only the number of neutrons changes (neutron emission), it becomes a different isotope of the same element.

- When the ratio of neutrons vs protons (n/p ratio) is near to 1:1 the element is stable.

- When the ratio of neutrons and protons deviates too much, the element becomes unstable and emits radiation to decay to a stable state, therefore it is named radioisotope or radionuclide.

Example: carbon

For example, carbon has the atomic number six because it has six protons. Carbon has 14 different isotopes (carbon-8 to 20 and carbon-22). All have 6 protons but a different number of neutrons. The number of neutrons can be calculated by:

Number of neutrons = (isotopic number – the number of protons)

Example: carbon-8 has 2 neutrons because 8-6 = 2. Carbon-20 has 14 neutrons because 20-6 = 14.

Good to know:

- Carbon 12 is stable, since 12-6=6 (proton-neutron ratio 1:1).

- Carbon-13 is also stable; the nucleus has enough energy to stay bound together.

- All other versions of carbon are unstable.

Making radiopharmaceuticals from radionuclides, example: carbon-11

Let’s look at the molecular answer to “What are Radiopharmaceuticals?” Carbon-11 can be used as a radiotracer for labeling compounds for imaging studies in, for example, oncology or neurology. One of the benefits of carbon-11 is that it can be incorporated into the compound when the compound already includes carbon. Therefore, the structure of the initial compound will not be altered. The stable carbon isotope will be replaced by the unstable isotope, making the compound suitable for imaging. A disadvantage of carbon-11 is the short half-life of only 20 minutes. The short half-life only allows visualization of the biodistribution of compounds with a fast uptake in the target tissue and fast excretion from non-target tissues. It also brings logistic challenges for the clinical trial.

Chelator and linker to build radiopharmaceuticals

In addition to building the radionuclide into the molecular structure, chelators and linkers can be used to bind a radionuclide to a targeting agent. The chelator or linker forms a bridge between a radionuclide and the targeting agent. The chelator makes labeling possible and prevents the radionuclide from moving freely in the body with the risk of increased off-target accumulation. Common chelators are DOTA, NOTA, NOTP, HBED, THP, TRAP, and DATA. The linker can act as a spacer between the radionuclide and chelator and targeting agent. Because both the chelator and linker can be of pharmacokinetic influence, especially for smaller molecules, seek advice from a specialist such as TRACER.

Interested in the labeling of your drug? TRACER can advise you and provide the production and logistics.

TRACER CRO

Ready to start preclinical or clinical trials with your developed radiopharmaceutical? Contact TRACER. Our specialists are happy to answer your questions. Maybe one of the commonly asked questions below applies to you.

- What Chemistry Manufacturing and Control (CMC) standards apply to my radiopharmaceutical?

- What regulatory requirements for clinical trials with radiopharmaceuticals apply to my compound? (CMC, preclinical, submission package, etc.)

- What surrogate radionuclide suitable for imaging will be best to replace my therapeutic radionuclide in imaging studies?

These types of questions require specific answers relevant to your compound. Get in contact with TRACER to learn more.

Contact TRACER

Read more about clinical trials for radiopharmaceuticals

Basics of radiopharmaceuticals FAQ

Below we’ve listed frequently asked questions and the corresponding answers. You may already be able to answer some of these based on the knowledge you have gained from this article.

How does nuclear medicine work?

Nuclear medicine uses the radiation of radionuclides for diagnosis (imaging) and treatment (therapy). A targeting agent may be used to direct the radionuclide to the desired location.

- For imaging, radionuclides are used that directly emit gamma photons or indirectly, via positron emission. Regions with a high uptake will be visible on the scan.

- For therapy, beta and alpha radiation are used to damage and eventually destroy the targeted tissue, such as a tumor.

What are radiopharmaceuticals in nuclear medicine?

Radiopharmaceuticals in nuclear medicine refer to drugs that emit radiation from within the body. So, basically, if a drug contains a radionuclide, it becomes a radiopharmaceutical. In research, non-radioactive drugs can be temporarily labeled with a radionuclide to study biodistribution and on-/off target uptake in clinical trials.

What are radiopharmaceuticals used for?

Radiopharmaceuticals can be used for diagnostics or treatment with a large variety of applications. Sometimes, a combination of diagnostics and therapy is used. For example, a diagnostic agent to stratify a patient’s eligibility to receive treatment with a therapeutic agent. This is called a theragnostic approach.

What are radiopharmaceuticals with an example?

We already discussed a few radiopharmaceutical examples, let’s dive deeper into that. Fluorine-18, a positron emitter, is used as a radiotracer for PET scans. An example of a radiopharmaceutical used in the clinic is 2-deoxy-2-18F-fluoro-β-D-glucose. For short referred to as [18F]FDG. The radionuclide 18F substitutes a hydroxyl group in the glucose molecule. This glucose analog will be processed as glucose by the body, with a PET scan, the added radionuclide can visualize uptake in different parts of the body. For example, a tumor or an inflammatory region has a high glucose uptake and thus will show on the scan.

What is the most commonly used radiopharmaceutical?

Technetium-99m (99mTc) is most commonly used as a radiopharmaceutical. It is a gamma emitter with low-energy electrons and a half-life of 6 hours. This makes it easy to work with and limits the radiation burden for the patient. The versatile and broad synthesis possibilities make it a Swiss army knife for diagnostics. Radiopharmaceuticals have been developed with 99mTc that can be used to image the skeleton, heart, brain, thyroid, lungs, liver, spleen, kidney, and many more. When you are a drug developer and you want to learn more about imaging the organs, cells, and functions of your interest or the biodistribution of your compound, contact TRACER.

Is a radiopharmaceutical a drug?

Yes, radiopharmaceuticals are considered drugs. To bring a new therapeutic radiopharmaceutical to the market, the process is similar to that of a non-radioactive drug. For a microdose/imaging radiopharmaceutical, the process and regulatory requirements can differ. TRACER, an imaging CRO, can conduct (pre)clinical trials, needed to bring your radiopharmaceutical to market.

What is the difference between radiopharmaceuticals and radioisotopes?

By answering the question, “What is a Radiopharmaceutical?”, you’ve learned that a radiopharmaceutical comprises a radioisotope. The term radioisotope is identical to radionuclide, meaning an unstable element that emits radiation upon decay. An element that can be incorporated into a molecular structure or part of a bigger construct to serve as a radiopharmaceutical. So, when comparing radiopharmaceutical vs radioisotope, radiopharmaceuticals refer to the whole structure, while the radioisotope is only the emitting part.